You’d think this lockdown would be an absolute godsend for introverted gamers; in fact, there are plenty of memes on social media that make that point. I saw one that said: “When your normal lifestyle suddenly gets called quarantine”. But it isn’t bliss for all of us. Yes, we get to stay in and have that gaming time we always desire and never get, but anxiety and depression are more crippling than ever. No more social anxiety, sure, but we’re still affected by the pandemic like everyone else. We’re still worried about loved ones, businesses, finances, our own personal health. Like the rest of the planet, we’re scared, and we’re struggling to cope. Where can we find solace?

Unsurprisingly, I found it in gaming. In two games, actually, that I stumbled across on the PlayStation Store: Celeste and Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice. Just to look at, you’ll find few similarities between the two; one is a colourful 2D platformer, and the other a hack ‘n’ slash adventure. Though once you’ve finished both, the parallels will be obvious. They both feature a protagonist with debilitating mental problems, and integrate this idea into the gameplay itself. In doing this, they prove how clever and profound games can be when developers put their minds to it. Their respective adventures are, to an extent, metaphors for overcoming their inner struggles. It is understandable to groan at this, but hear me out. You might find them just as uplifting and consoling as I did.

Celeste, released in 2018, is the most difficult platformer I’ve ever played. Players take control of a young Canadian woman called Madeline, who – like most of us – doesn’t know what to do with her life. Naturally, she decides climb Mount Celeste, a magical mountain based on a real place on Vancouver Island. Navigating Madeline up the treacherous mountain is challenging, especially if you’re shit at games like me. (I checked the average time to complete the main story; it took me an extra three hours) The mechanics of the game are simple – jumping, dashing, climbing – but you have to be inventive and resourceful in combining these actions. Even seasoned gamers will die, a lot.

And yet, the genius of Celeste is in the way it views failure. Early on in the game, we are told to view our death count with a sense of pride. It means we are learning, and it shows our determination. We respawn from a death instantly and seamlessly, so it’s difficult to get stressed. This idea melds perfectly with the story. Madeline has her heart set on reaching the summit of the mountain; she’s one of the most stubborn characters I’ve ever encountered. However, she is constantly being told to give up, and the relentless way she pushes on is inspiring. It creates a sense of empathy between player and protagonist that I’ve never experienced. Her determination becomes your determination – there were times when this was the only thing stopping me giving up.

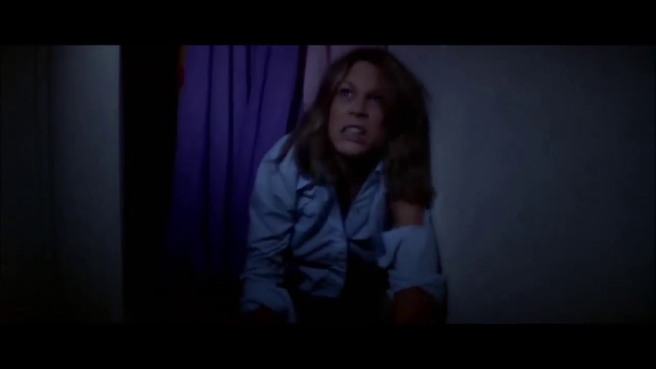

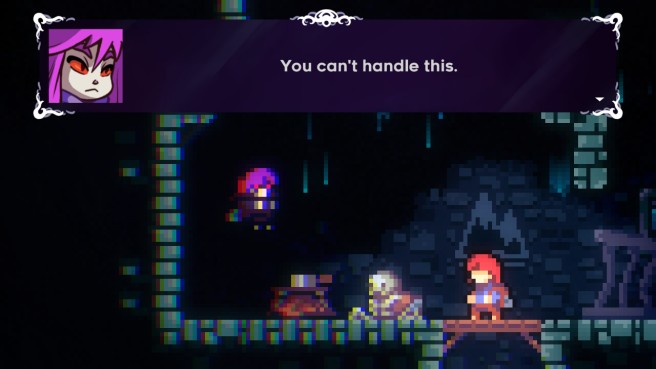

This is because the biggest obstacle for Madeline is herself – a voice inside her head. Madeline suffers from severe anxiety and depression, and climbing this mountain is an attempt to overcome that. (there’s that metaphor mentioned above) Celeste Mountain has a mysterious power, which allows people to meet their emotions in a personified form – think of the Pixar film Inside Out. Madeline spends most of the game running away from her personified anxiety, a cynical Madeline in gothy attire – a bit of a visual cliché, but it’s hard to care – who she first meets in a mirror’s reflection. At the end of the game, however, she faces this other Madeline head on, and calmly talks to her. When they accept that they’re two sides of the same person, and decide to work together, Madeline gains a new power.

For me, it represents accepting your mind, warts and all, getting to know it, and understanding it, to more effectively climb the stressful mountain of life. Whether you read into it this much or not, there’s no doubt that Celeste is a comforting meditation for stressful times.

The idea of accepting your troublesome mind is also explored in 2017’s Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice. Set in 8th century Scandinavia, players take control of Senua, a young woman from the Pict tribe. She has travelled to Helheim, it seems, to save soul of her deceased lover. The plot is intentionally vague, as is the gameplay – there are no tutorials, you have to figure everything out yourself. What soon becomes obvious is that Senua suffers from an extreme form of psychosis; eerie voices constantly talk to her, and visual hallucinations lurk around every corner.

Although you have to work everything out yourself, the gameplay is simple; exploration and puzzle solving, interspersed with the occasional combat. What the game ingeniously does, though, is incorporate Senua’s mental state into the gameplay. In a flashback, we learn that Senua’s mother suffered with the same illness, but told her daughter there was nothing wrong with seeing the world this way. In fact, it can be helpful; she calls it “the sight.” Many of the puzzles in the game require Senua to look at things from a strange angle. Occasionally there are floating fragments that need to be looked at from a certain position, and once Senua sees them correctly, they’ll become, say, a bridge. This nicely shows that having a different mind can be a useful thing.

This isn’t to say that the game sugar-coats psychosis as some kind of superpower – far from it. When Senua’s panic and fear become intense, the screen gets blurry with occasional flashes of disturbing images. To make things worse, the voices get louder, and their statements become negative and despairing; “you’re dying, you’re lost, you’re dying…” It is recommended to play the game with headphones because there is a 3D sound feature. The developers consulted with numerous mental health advisors to produce a realistic simulation of psychosis. The floating voices might be too intense for some, but, like Celeste, we feel a genuine sense of empathy with our protagonist – we feel like we’re inside Senua’s head. And, like Madeline, she has an inspiring amount of willpower and grit.

Without giving too much away, both games have positive and uplifting endings, so if you find the stress too much to endure, bear this in mind. That being said, they’re realistic – there’s no suggestion that you’ll just get better once you’ve overcome an obstacle. Madeline’s anxiety is never “cured”, so to speak. At one point in the game she literally hits rock bottom – that is, the bottom of the mountain, and the pits of her emotions. It’s realistic, too, showing that taking care of your mental health can be a bumpy ride – it isn’t linear, but often one step forward and two back. In fact, there have been two additional stages added to Celeste in the two years since its initial release, chronicling Madeline’s future, one of which focuses on a period of grief. And a sequel to Hellblade was announced at the end of last year, so Senua’s story isn’t over either. Mental issues are a long and arduous journey, and it is comforting to see games addressing this realistically – especially in times like this, when our mental endurance is being tested like never before.